Wednesday, April 29, 2009

Are You Offended? Does it Matter?

This video is one of the clips from the sketch that ended Chappelle's Show.

That might be an oversimplification, but it was this sketch--the racist pixies--that Chappelle has since cited in interviews as the reason he left the show (and walked away from $50 million). This is the topic of my paper for this class; I want to explore what it is about this sketch, amongst a plethora of envelope-pushing racial satire, that pushed Chappelle over the edge.

I don't think it's the content itself. This content, while possibly a little racier, isn't that much different from previous content on the show. Chappelle has always been one to make his audience a little uncomfortable with the social atmosphere around them, and, in my opinion, that's the whole point.

He's said in interviews that the problem was the audience, or at least one member of it. While filming the black pixie (who Chappelle portrays in blackface) one member of the audience laughed "particularly long and loud" (interview with Time) and made Chappelle uncomfortable. Chappelle began to question "if the new season of his show had gone from sending up stereotypes to merely reinforcing them" (Time).

There's the problem: Chappelle can't control what it is his satire does. He always runs the risk of reinforcing stereotypes. He just became more aware of that risk as his audience broadened and he became exposed to the different readings present in his work. As one scholar I'm reading puts it: "I know what I'm laughing at, but I don't know what you're laughing at" (Haggins, Laughing Mad, 205). Chappelle cannot control his audience, not even that one physically present in his studio. He certainly cannot control that audience that grows infinitely larger as DVDs are bought and sold, as youtube videos are shared.

I really like Dave Chappelle's comedy. I think that Chappelle's Show did a great job of pushing the boundaries in a way that potentially opened eyes to injustice and absurdity. Discussions of race in America are often muted, and Chappelle's is certainly not. As Haggins says later in her essay, the "task of the provocateur is to incite dissension--to make people question things as they are--it's not necessarily his job to provide the answers" (236).

I don't know how I feel about this sketch. He was obviously uncomfortable with it and never wanted it aired. Comedy Central released it as part of the unfinished third season in the "Lost Episodes," which I had refused to watch before because I thought it was wrong of them to release them. I watched it for this paper. I think it is important to tease out the subtleties of satire and try to figure out where the line is. How much of this is completely up to the audience? How much of an audience can a performer control?

Thursday, April 23, 2009

Oh Humor, You're Such A Fickle Creature

How many things have to go exactly right for a piece of comedy to succeed? The audience has to be in the right frame of mind, that is, primed for laughter. The material has to be timely so that it can be of interest, and that means that jokes must constantly be re-written to adapt to the newest demands of the audience. At the same time, however, the comedian is saying nothing new; instead, the joke has to be refreshed into an utterance that meets all these other demands while still pulling from a general pool of past comedic (or non-comedic) performances.

Are other genres this demanding? And what is it that allows some things to remain funny years later (and out of their contemporary contexts) while others fizzle in weeks?

It made me think of some contemporary poetry. Obviously, we have an affinity for poetry that can lasts centuries; it doesn't necessarily have to be timely. However, is it possible to make it too timely to survive into the future? I'm thinking of a poet named Terrance Hayes, who I think is a tremendous writer. He visited one of my creative writing classes when I was an undergraduate. His poems have a lot of cultural references: Wal-Mart, song titles, hip hop artists. I wonder if this timeliness (which adds a lot to them in their contemporary context) can be a liability for posterity? Does humor always have to skirt this line?

Thursday, April 16, 2009

Do I Expect Too Much?

However, I first wanted to blog about why this topic interests me in the first place. Humor, to me, is at its best when it has a social purpose. I think that all works of creative expression can serve in this way, and humor is perhaps one of the most powerful. It is a great work that can make you laugh and later make you think.

Racial humor often works in this way. Gender humor does, too. But there are risks.

Self-deprecating humor can often act as a parody of the real injustice toward the group. When Chris Rock makes jokes about white people using the n-word, he is parodying a real issue. What does this parody do? Who does it reach?

Parody can draw attention to the real problem in a new way. People may not have recognized their own participation in the problem before hearing the joke. Often, though, I think the effect is much more subtle. Sometimes the audience doesn't really recognize themselves as part of the problem, but they can still be enlightened by a comedic performance on the topic.

Who's the audience, then? Is it humor's responsibility to open the eyes of people who are doing wrong? Probably not. An overt racist is probably not going to be watching Chris Rock in the first place, and even if he/she was, it is unlikely that the show would cause any dramatic changes in thought.

People who recognize the injustice but are victims of it may find cathartic release in humor. It is a defense mechanism (a common theory about how humor works). But pointing out the obvious in a humorous way isn't necessarily socially helpful.

What about people who just haven't recognized the problem in the first place? This seems to be the audience that stands to benefit the most from this sort of parody. People who are neither victims nor perpetrators stand in a position to do something about injustice. Can humor help them recognize both the problem itself and their unique position to help solve it?

Am I asking too much of humor when I look at this possibility? I know that not all humor has this goal in mind, and I think that there are other equally valid goals, but this is the one that is most interesting to me.

Thursday, April 9, 2009

Excising the Joke: A Problem for Scholarship

In class, we've taken a few different approaches.

For many of the stand-up comedians we watched full length shows of their performances, analyzing them (mostly) in their entirety. Though we may have focused on particular jokes momentarily, the brunt of the discussion centered around thematic elements: Chris Rock's use of gestures, Ralphie May's tendency to make the audience uncomfortable, etc.

We took a similar approach when we looked at the female stand-ups, but we only got short glimpses (five minutes!) at most of their work. The conclusions we drew, to me, highlighted the small sample we had to work with. They seemed contrived, forced, and not very insightful. Perhaps a longer view of these works would have provided much more illumination into the elusive female stand-up.

For written works, for a few authors we have read multiple pieces. Similar to the longer stand-up, reading multiple works allows for a more holistic view of the writer's use of humor. This enabled us to make (as we did in class on Wednesday) a catalog of "typical" tropes for individual authors or for an entire genre of humor. As we discussed, the Southwestern comics used dialogue, played on the country v. city tension, and frequently depicted slapstick.

In other written works, we had smaller sample sizes, but for some reason these were more fulfilling scholarly endeavors for me than the short clips of stand-up. The pieces, even though not as revealing as a series of the author's work, were typically complete, stand alone works. This allowed insight into the way that individual authors used familar tropes successfully (or unsuccessfully).

We haven't, however, done much close textual analysis of individual jokes. The book I am reading for the review works almost entirely from this methodology and I am questioning its validity. For example, the author, John Limon, closely analyzes a joke from Carl Reiner/Mel Brooks skit to conclude that a "male-male comedy team is an odd couple, and an odd couple is a union that cannot declare its essence to be this or that" (49). He extends this to an examination of the abjection of homosexuality in these duo comedy teams.

Regardless of my opinion on the conclusion, I do think this method is questionable. Can a single joke be that revealing? Jokes, as Limon himself points out, are more audience and context-dependent than just about any other art form. Doesn't taking a single joke in this way negate that context and radically alter the audience? What about all of the performance leading up to this joke? What about all of the performance moving away from it?

We do similar things with other literary criticism. I have written a paper about a single line of a poem. Somehow that doesn't seem as questionable to me, and I'm not sure why. Perhaps because the poetry is less audience dependent than a comedic performance?

In Defense of Studying Humor

When you study the Civil War, you don't expect to get bloody. When you study genetics, you don't expect to get cloned. Examination, by its very nature, alters your perspective on the thing you are studying in such a way as to make it no longer the experience it was "meant" to be.

But we do it anyway.

Here is a (incomplete) list of the things we've determined about humor so far:

1. It is often timely.

2. It is commonly used by in-groups.

3. Everyone's opinion on what is or is not funny differs.

4. It often pushes social boundaries.

5. No critic can agree on what makes something humorous (see 3).

Okay, so, our position as students studying humor makes us:

1. View pieces that are often no longer timely.

2. Definitely step outside of the in-group. Even if we are part of the demograph the original act was meant for, when we are in the classroom we are part of a different group, one I'm sure no comedian has in mind as the audience. Perhaps this is why I laughed more when I was watching the stand-up or reading the stories at home than I did in the classroom; I was in a different group. Essentially, I was a different audience.

3. We're trying to have a conversation as a class full of diverse opinions. This can be great as long as we don't approach it as something we have to agree on to understand.

4. Pushing the social boundaries is the reason to study humor, at least in my opinion. If it served no societal function, then maybe a class on it should just be fun, but the fact that it can be a vehicle for many larger issues makes it a field worth trying to understand.

5. We're English majors! Surely we can deal with critics who can't agree with one another.

In order to enjoy studying humor, our expectations have to change. I admit that coming in, I wasn't quite sure how to approach this task, and at times I wanted to just watch the clips, read the story, and be the audience the creator probably intended, but that doesn't help me understand humor. In other words, if the class was too fun, we probably wouldn't be doing a very good job.

Friday, April 3, 2009

Why Stand-Up?

As the selections we read for this week prove, women can be funny in print. (I think they can be funny in stand-up, too, but so many of the examples we watched felt forced, out of place, like they were trying to fit in at the boys club they didn't belong to.) Women can also be funny in situational comedy, which I think parallels with many of the stories we read recently.

"Xingu" and "The Petrified Man" are good examples of this sort of situational humor. In both of these stories, the narrative revolves around character interaction. The humor is largely in creating the characters and the back-and-forth dialogue that transpires between them. We see this constantly in sit-coms.

I was reading a piece once (though I cannot remember the title or author, I know, what a horrible grad student!) that talked about the difference between women's mode of composition and men's. Women were more circular, less direct. If women write differently, is it any wonder that they would be funny differently as well. If women "cannot be funny" as some of the critics of female humor have said, then it's because we're measuring from a very narrow perspective.

Wednesday, April 1, 2009

Quit Whining

I guess it could have been there subtly before, but the repetitive themes of the stand-up were getting a little grating. Boo-hoo women feel fat. Boo-hoo men don't appreciate us.

Parker's "The Waltz" does a great job of pointing out the fact that women need to take responsibility for their own happiness.

Friday, March 27, 2009

The Misfits

Chris suggests vodka tasting and nude calendars; Mrs. Roby rejects asinine readings and challenges the women's "intellectual" standards. In the end, Chris is a hero of her intimate circle, successfully altering the women's views of themselves and their traditional roles. Mrs. Roby, however, is cast out of the group; her rejection of the norms is unacceptable.

We've noted that women are often misfits when it comes to stand-up, too. Margaret Cho doesn't dress like a lady, and she certainly doesn't talk like one. Her frank discussion of her sex life would surely leave even Chris blushing in shame. Jeanene Garafolo is a stand-up who rejects traditional roles by refusing to be sexualized in order to acheive fame. Her dress, attitude, and general demeanor set her outside of the traditional view. Even the stand-ups who may look the part of the traditional woman bend the rules.

However, as I mentioned in my last post, some of these women don't seem to be breaking them.

Again, I'm not suggesting that comedy's role is to change society, but it certainly can't hurt. As far as my personal preferences go, I'm finding myself much more attracted to comedy that does seem to have some more aggressive agenda: addressing racial stereotypes, breaking down gender barriers, mocking consumerism. While a joke that's just a joke is fine, a joke that makes me think is better. If that joke makes me think about something that needs to be changed in the world, that's even better still.

I think that there is something different about the way Chris and Mrs. Roby wear their misfit label, and in that difference I feel there is a more ambitious social commentary. Margaret Cho does not do much to break down barriers for women (though she does possibly do more to break down barriers for the gay community--though I'm not entirely convinced she's not merely bouncing around in those stereotypes as well--I'd have to see more of her acts). Neither, despite my general appreciation of her work, does Jeanene Garofolo. In order to be a socially progressive comic misfit, then, how do women successfully break those barriers without merely fitting into them in new ways?

Monday, March 23, 2009

Does Pushing the Boundaries Reiterate Them?

Both of these women depend on the boundaries of gender stereotypes in order to be funny. Without the stereotypes that women are supposed to be shy, docile, and quiet, neither of these "shock" comedians would have a show.

Cho's humor depends upon taboos about women's sexuality and female body issues. Her jokes about women's relationship with weight, experimental sexual clubs, and her period all depend on a certain image of a what a woman is supposed to be. As Cho herself says when talking about the images of stick-then models, "If that's what a woman is supposed to be, maybe I'm not one." This same theme is at the heart of her entire performance. Without the preconceived notions of femininity and female actions, her act would not be funny at all.

How much, then, does her act really push the boundaries for women? I'm not necessarily saying that it's supposed to, or even that comedy has that responsibility at all, but there does seem to be a role for comedy to perform a sort of social policing. Comedy can be used to question stereotypes. So, for the sake of argument, let's say that female stand-ups want to question the stereotypes about women. Does depending on those stereotypes to be funny break them or reinforce them? Does it depend on who's watching? Cho seems very aware of her audience, constantly referring to the different factions who may respond differently to certain parts of her performance (such as when she says the gay men are plugging their ears at the talk of her straight sex life). How does this knowledge of audience expectation play into the stereotypes she is using?

Monday, March 16, 2009

Dramedy?

The whole premise of Calendar Girls begins over raising money in the name of a recently deceased cancer victim: a main character's husband. Furthermore, his death does not take place off-screen, an alluded to tragedy. We, the audience, see this man; we get to know him; we feel the pain of his death. For me, that pain was very pronounced throughout the film watching the wife's character react at different points. Her cry that "he didn't drink beer" struck me as very tender and sincere. When she breaks down in Hollywood, I was very touched.

This is the most overt sign of drama in this "comedy," but it was certainly not alone. Chris's son's reaction to her stripping is very dramatic and serious. One woman's dissolving marriage is shown in realistic (and not very humorous) ways. The fight between Chris and her best friend over the calendar is painful to watch.

The Full Monty seems a little more balanced in its humor and drama, but it still has some very serious scenes. Suicide attempts. A funeral. A man unable to deal with his insecurities at risk of losing his wife. A man unable to provide for child support at risk of losing his son.

This is not the stuff of comedy, at least, not in the way its displayed.

There are, of course, comedies that deal with serious subjects. In Tommy Boy, an entire town is about to lose their jobs, but I don't think there's much that is "serious" in this film. In Knocked Up, a woman deals with an unexpected pregnancy and the thought of single-motherhood, but there are very few serious moments that address this issue (although, admittedly, there are a few more than the previews would suggest). Weekend at Bernie's is all about a man dying, but we're not particularly sympathetic to that death.

What then, makes something a comedy and something a drama? I think back to some definition I was given in middle school (I think it was connected to the Greek definitions): if the characters are worse off at the end, its a tragedy/drama, if they're better off, it's a comedy.

This doesn't seem to hold up in our contemporary viewings, however--at least not for me.

The connection this had to Abby's post (for me) is that I couldn't think of any female-driven comedies that didn't revolve around men/love/marriage that weren't of this "dramedy" category. I thought of A League of Their Own, but there are very serious moments in that movie. Fried Green Tomatoes has a lot of funny moments, but I'm not sure what side of the divide I'd palce it on. Does this connect back to the stereotype that women can't be funny? In order to display humor, does female comedy have to a) revolve around men or b) revolve around drama?

Respectable Strippers

Chris's son is absolutely devastated when he discovers what his mom's been up to. We see him, in one of the many melancholic scenes in the film, throwing the newspapers with the cover story over the edge of a cliff. He is humiliated and angry with his mother. Though we get some hints that his father has tried to talk him out of this attitude at the very end of the film, we see no reconciliation of this problem.

In The Full Monty, on the other hand, Gaz's son only briefly rejects his father's stripping. (Even then, it's clear that Nathan undergoes something a little more traumatic than Chris's son ever did. After all, Nathan was watching his dad strip in an abandoned parking lot; all Chris's son did was see her picture in the paper.) The rejection does not last, however, and Nathan becomes an active participant in the scheme; in the end, it is his firm words that send his dad out on stage.

What's the difference? Is it gender-based?

I'm not sure that it has to be gender-based, but I think it certainly might be. Chris, being a woman (and an older, married one at that) is not supposed to be stripping. Neither is Gaz, but his performance is met with laughter and jokes, not shame. While Chris's husband understands the artistic and independent nature of her decision to strip, her son does not. Furthermore, there is little "art" to Gaz's performance, but that doesn't seem to stop the majority of the people in his life from supporting him (even his ex, who supports little else that he does).

This could be a commentary on the gender roles of parenting. Chris, as a mother, is supposed to be nurturing, dometic, docile--a role that she appears to have been uncomfortable with even before stripping (thus her problem with the women's club to begin with.)

At the beginning of the movie, Gaz is also not performing in the traditional role of father; he is not providing, and his son sees him as unstable and a little crazy.

Chris, then, further removes herself from her perceived role as mother by stripping for the calendar. Gaz, on the other hand, solidifies his role as father by using it as the opportunity to finally provide for his son. This would explain why Chris's act alienates her from her son while Gaz's brings him closer to Nathan.

One final thought about this observation: would it have been different if Chris had had a daughter? I can't remember what the woman's name was, but one of the women who stripped for the calendar was frequently shown with her daughter--a daughter who fully supported her decision. Is there something that makes a daughter more able to understand her mother's actions than a son? Is this why Nathan was able to relate to Gaz?

Tuesday, March 3, 2009

If a Tree Falls in the Woods . . .

Sunday, March 1, 2009

"Mommy, why does Eddie Murphy need a shoehorn?"

t of incongruous message was obvious to me when I watched Bob Saget. I associate Bob Saget with Full House: a well-mannered, fun-loving guy who just wants to take care of his kids. This image made him perfect as a host on America's Funniest Home Videos. I obviously knew that the image was a persona, but it wasn't until I saw The Aristocrats that I really started to pick that persona apart.

t of incongruous message was obvious to me when I watched Bob Saget. I associate Bob Saget with Full House: a well-mannered, fun-loving guy who just wants to take care of his kids. This image made him perfect as a host on America's Funniest Home Videos. I obviously knew that the image was a persona, but it wasn't until I saw The Aristocrats that I really started to pick that persona apart.

The two images are impossible to reconcile if you believe either of them to be the "real" Bob Saget. But comedians' personas are difficult to deal with; we expect them to be themselves, or at least somewhat hyperbolic versions of themselves. In the book I am reading for my book review, Stand-up Comedy in Theory, or, Abjection in America, the author notes that

"comedians are not allowed to be either natural or artifical. (Are they

themselves or acting? Are they in costume?) Reality keeps returning to stand-up

performance, but the deepest deisre of stand-ups is to be, with respect to their

lives, unencumbered"

Friday, February 27, 2009

Bad Reputation

When I did finally watch it, I didn't really like it, but I also didn't feel like two hours of my life had been stolen. I laughed a few times, I thought that it was somewhat interesting social commentary, but overall I felt it was just stupid comedy. I watched it again a few months later, and it was much, much better. Since I already knew what was happening, I started noticing a lot of small details. This wasn't just stupid comedy. The creator of this film had put some thought and consideration into this. The advertisements (like "Uhmerican Exxxpress: don't leave home") were wonderful mini-parodies. The comment about the lawyer's dad knowing someone on the admissions board of Costco law school was hilarious. Rita's kindergartenesque paiting of Joe was a nice finishing touch. Most of all, the satire came through more clearly, and I found it to be convincing.

How many people would give it this second view, though? And how many people never saw it to begin with because of its bad reputation?

The layering is probably no accident. I didn't know until reading this review that the creator of Idiocracy also made Office Space. According to the article, Mike Judge was disappointed in the fanhood of Office Space because the people it mocked became its biggest fans, and they didn't recognize the second, deeper level of satire. The reviewer notes that "Buried just below the surface, however, is a critique of the modern American workplace and of the materialism that makes us slaves to our machines." On the surface, however, it is a silly, farcical comedy about office life.

This reviewer goes on to say that Judge went in the opposite direction with Idiocracy, creating the "feel-bad comedy of the year." He goes on to note that it is rare to watch a movie that openly challenges your beliefs, and that Idiocracy does just that.

It didn't do so well at the box office. It had limited release and didn't even cover its production costs.

All of this is leading up to a question about the effectiveness of satire. It seems like a very fine line to walk. You have to make your satire apparent enough to be understood while still making it veiled enough to be entertaining so that other people will watch it. In the case of Idiocracy, where the creator is clearly telling the audience something they probably do not want to hear, the entertainment factor is incredibly important. I think that is why I didn't like it the first time I saw it. I had to dig through a lot of farce to find the satire. Once I did, however, I was impressed. I wonder how the viewing world at large did with this film. Did it convey the message it needed to? Did it reach the people it needed to? Does it run the risk of preaching to the choir? Or does the scatological humor, slapstick, and "low comedy" attract the audience who the message is aimed at? If it does, does that message actually reach them?

Tuesday, February 24, 2009

Beef Supreme channels Harpo?

Is Beef Supreme the 21st century answer to Harpo Marx? He doesn't speak. He uses expressive facial and bodily expressions to entertain an audience. He has particular props. He is athletic and acrobatic.

In addition, he embodies the part of slapstick that makes it unfunny to me: violence.

This isn't the only slapstick in the film, but I think that Beef Supreme is the only actor in Idiocracy that seems to be functioning in a role of pure physical comedy.

Furthermore, Beef Supreme functions in a way similar to the Marx brothers in that he's participating in a role that provides societal critique. In Duck Soup, Harpo represents a critical view of social norms and motives. His insulting way of dealing with adversaries leads to a critique on war in general, questioning the way wars begin as well as the sacrifices of the individuals involved. Beef Supreme functions as a critique on, among other things, celebrity. When he first appears from the rubble, there is a group of girls swooning a la Beatle-mania. The crowd goes wild at the sound of his name, and they react quite enthusiastically to his charade of hunting down Joe.

Obviously, Beef Supreme is a minor part of Idiocracy, but I can't help but notice the similarities from the genre of comedy we've been watching in class, similarities I wasn't really expecting to see.

Thursday, February 19, 2009

Ow!

This does not sound like the start of a funny story to me; it sounds like abuse.

I'm a little squeamish when it comes to violence. I'm too empathetic. When I see someone, for example, get his hand cut off on the screen, I grab my wrist. In class, during the umbrella scene, I was holding my stomach; this was the worst scene because I couldn't see the Stooge (Curly, I think) beneath the sand. Was he okay? Dead? Screaming with a mouthful of sand?

In a much earlier post (my first or second), I commented that I didn't find slapstick very funny. I also noted that I thought slapstick was funnier when it was written or when it was a cartoon. Then I posited that perhaps this was because I could imagine it rather than see something so outlandish and unbelievable on screen. Now, I have a different theory; cartoons don't get hurt.

I understand, of course, that the Stooges are not actually hurt, but they are actually people. This reminds me of America's Funniest Home Videos. I hardly ever laugh at them, especially since they've become less babies and animals doing cute things and more people falling off of roofs, riding bikes over cliffs, and getting accidentally hit with baseball bats.

Pain isn't particularly funny to me, and violence is flat out disturbing. It was mildly amusing to see one of the Stooges get accidentally (and usually less severely) whacked with a random object. It was much less amusing to see Mo (right? I don't have the names straight) beat his "friends" and threaten to "murder" them or "chop his head off."

Does anyone else feel this way? Is violence funny? Is it okay because they're not actually hurt? I remember watching the Three Stooges as a kid; is that the right impression to send to children?

Tuesday, February 17, 2009

The Reality of Humor

Instead, it seemed to me to be a dark glance into the disgust and anger this man felt against the world near the end of his life. I haven't seen the whole show, so I can't comment on a cohesive theme here, but he was speaking from a giant graveyard. It seemed to me that Carlin was trying to put some perspective on the life he'd seen and make it all make sense. The end result: it doesn't. As we discussed in class, it's impossible to be a modern man (one made up entirely of taglines) and still have substance. What starts out as clever wordplay and amusing oppositions in the first clip ends up as the rantings of an angry old man.

Sure, there's some humor in this rant, but rather than glimpses of the American condition highlighted through humor it seems to be the other way around: glimpses of humor shining through an otherwise bleak view of the American condition.

He did bring up a point that interests me, though.

I have a rather unhealthy fascination with reality TV. Not an attraction, mind you, but a fascination. I don't understand it, and I occasionally watch it in awe, like I would observe a lion killing off the slowest gazelle: wincing, feeling for the gazelle, a little disgusted, and a little embarassed at watching this carnal display.

When I heard Carlin talk about the suicide channel, it didn't strike me as funny at all. It struck me as true. Our culture has become so obsessed with reality TV that people just might be willing to throw themselves over the edge of the Grand Canyon for their fifteen minutes of fame.

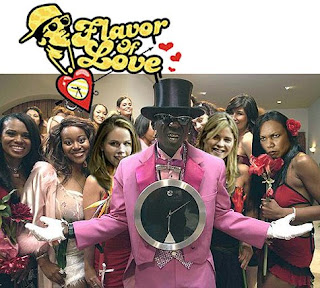

Now, I realize that there are different types of reality TV. I'm not so much thinking of Survivor, American Idol, or the Biggest Loser. I'm thinking of a spectrum that at best is America's Next Top Model and at worst is something like Flavor of Love or the Bad Girls Club. Shows where people line up (literally) to audition for the chance to make complete fools of themselves on syndicated television. Shows that revolve around acting as uncouth, promiscuous, cruel, shallow, or just plain stupid as possible. And we line up to watch them. Don't believe me? VH1 and MTV certainly seem to think we watch them; their entire line-up is hour after hour of this self-loathing.

Which brings me to wonder, is it comedy? I think that most of the people I know watch it for a good laugh. Maybe it's comedy in the way that Thomas Hobbes describes humor: "sudden glory arising from some sudden conception of some eminency in ourselves, by comparison with the infirmity of others." Do we watch because it makes us feel superior? This seems reasonable to me, but then why do the shows exist at all? Why are there people willing to go on them? It seems to be that the participants feel superior by going on the shows in the first place. This creates a confusing paradox. How can both the specator and the spectacle be superior? What outlet does reality TV really serve and does it fit into humor theory?

Thursday, February 12, 2009

Let Me Try Again

There are several things that I think Grawe gets right (or at least as right as anyone can get in a theory of humor, which seems to be an elusive thing). I think that it's an intelligent observation to say that comedy is representative of life; we can usually see more of ourselves and other real people in a comedic protagonist than those of other genres. Likewise, comedy often doesn't require an outlandish plot to be successful.

Secondly, patterning is certainly seen in many art forms. I think that the way Grawe describes patterning and the themes it can reveal is very accurate.

Though I'm not entirely convinced, I'll even entertain the fact that comedy's main goal is to show that humanity will survive. It is when Grawe starts exploring this more closely that he loses me.

Grawe tells us that there are three types of comedy with a positive protagonist (heroic, everyman, and buffoon) and three with a negative one (villian, butt, and fool). He also says that these progressively blur into one another. To connect these categories to his earlier assertion that comedy is a statement of the faith that humanity will survive, he makes some generalizations. Heroic comedy "asserts that mankind's survival is based on exceptional individuals and their values or abilities" (35). Everyman comedy's assertion "is that the human race survives and must survive not because of any one particular and extraordinary talent . . . but because people are social creatures who can use the special talents of every individual" (37). Buffoon comedy asserts "both the good news and the bad news" (42) and shows us "people surviving in spite of themselves" (17). The negative protagonists show us overcoming the self-destructive individuals in society in similar progression. These distinctions work very well for the examples that Grawe gives, but most of his examples are television/movies and all of his examples involve multiple characters who interact with one another. Also, the comedy that Grawe discusses creates a microchosm of society; the actors in The Waltons are not supposed to be the actors when we watch them--they are the Waltons.

While I completely agree that all stand-up comedians create a persona in order to do their acts, I still don't think this is the same as the actors in a movie or television show. We know that this person is up there telling jokes. We are not watching a "fake" world that is supposed to be real (characters instead of actors) and drawing comparisons to the real one. For this reason, it doesn't seem to me that stand-up comedy can fit in this. If Chris Rock or Ralphie May represent one of these characters, how does that show us human survival. Let's say, as we started to in class, that Chris Rock is an everyman. He is a single person standing up on the stage telling jokes; in what way does that illustrate that we are social creatures who will survive because we have the ability to use other's talents? Perhaps he's a hero, but then what way does that act illustrate that we will all survive because of his extraordinary abilities? Is he going to tell jokes to chase away the meteor or alien attack? It just doesn't fit to me.

I think that comedy, like all art forms, cannot be categorized this specifically. Grawe tries to keep it broad, but his prejudices come through. When he thinks of comedy, he thinks of situational comedy in which people pretending to be fictional characters (or books with other characters created in them) interact with other fictional characters to provide a window into the real world. He leaves out satire. He leaves out stand-up. He probably leaves out several other kinds of comedy. In the end, he has done nothing more than the critics he so harshly chastizes in his first chapter: created a theory that accounts for a small piece of comedy.

Wednesday, February 11, 2009

The Other Side of the Ralphie May Spectrum?

First, a caveat: I recognize that my liking Chris Rock's comedy definitely tints the way that I view these pieces. However, I still think there are some striking differences that deserve attention. Also, I wholeheartedly believe Ralphie May should be able to tell whatever jokes he wants; I'm very supportive of free speech. Just don't expect me to laugh.

1) The audience- Ralphie May's absolutely blatant (and to me disturbing) singling out of the one black woman in the audience was very different from Chris Rock's interactivity with audience. I recognize that some light-hearted ribbing of the audience is part of stand up culture. However, when Chris Rock makes fun of the white women who are trying to explain to their (presumably white) husbands why they laughed at the joke about sex with black men, he's not singling them out individually (partially because there's more than one to single out--another striking difference from Ralphie May's distinctly racially solidified audience).

2) The point- While Ralphie May later explains that he wants to push his audience to the edge of the line of decency and question their own sense of humor, he makes no such disclaimer before telling the joke about the black theater. The point of that joke, to me, seems to be that he knows a secret about this subculture that his white audience does not. They are having this other world illuminated by listening to Ralphie explain ghetto hair cuts and stereotype black accents. He perpetuates difference and separation through this dichotomy. Chris Rock, on the other hand, is talking to a diverse crowd, and much of his humor centers around the interaction between the two (or more) cultures. While his discussion of the n-word (which I choose not to use for complicated and probably not interesting reasons, though I do not object to its use by others; words, after all, are only words), certainly pushes the same line of decency that Ralphie refers to, the effects are entirely different. Chris Rock focuses on interaction; Ralphie May centers on separation.

3) Race of the speaker- We discussed in class that it is often more acceptable for the minority to make fun of the ma

jority, but not the other way around. This makes sense to me--especially when the majority has used its power for centuries to degrade the minority in every categorical way possible. This doesn't just apply to race, and it's also true of groups that are making fun of themselves. When Jeff Foxworthy makes fun of "rednecks," many find it funny. If a Wall Street executive made the same jokes, they wouldn't. So, when Ralphie May, as a white man, makes fun of black people it has a different effect than Chris Rock, a black man, making fun of white people (which again, in the skit we watched, I'm not convinced he did--he more made fun of the interaction between white and black culture than white culture itself).

jority, but not the other way around. This makes sense to me--especially when the majority has used its power for centuries to degrade the minority in every categorical way possible. This doesn't just apply to race, and it's also true of groups that are making fun of themselves. When Jeff Foxworthy makes fun of "rednecks," many find it funny. If a Wall Street executive made the same jokes, they wouldn't. So, when Ralphie May, as a white man, makes fun of black people it has a different effect than Chris Rock, a black man, making fun of white people (which again, in the skit we watched, I'm not convinced he did--he more made fun of the interaction between white and black culture than white culture itself).

Friday, February 6, 2009

Oh The Dichotomies!

Eddie Izzard's act set up a few different dichotomies: British v. American, crossdresser v. (what's the opposite of a crossdresser? non-crossdresser?)

Cook's work clearly takes up the British v. American point of view (as the narrator tells us, even his best experience in America was "Not half so good as English beer" (26) and most of the time the expectations he has from his British lifestyle ruin any chance for a positive experience in America).

When we add persona to the mix, however, it becomes much more complicated. When Eddie Izzard makes fun of Americans, it's a clear us v. them set up. But he then goes on to make fun of his fellow countrymen (such as when he mocks England's insufficient funds for participation in the moon race). He creates a persona that allows him to make fun of both sides (and that's a good thing, since this particular piece of stand-up was performed for an American audience), but where does that leave him in us v. them? His audience doesn't necessarily consider him one of them, and his crossdressing further removes him from them.

The persona of Cook's narrator, too, plays a large role in the way "The Sot-weed Factor" is read. This narrator shows obvious condecension for America and all things American from the very beginning. An American audience has no doubts that they are being cast as the "them" and that this "us" wants no part of it. There is none of the self effacing humor that arguably allows Izzard to get away with mocking Americans. Instead, Cook's narrator becomes the butt of the joke. Cook develops a character with outsider status and uses it to create the humor. We laugh because he's not one of us; the us v. them gets turned around against him as he fails to fit into his new environment.

Monday, February 2, 2009

I'm Funny! Right?

I hadn't put much thought into the gender gap of humor before. Sure, I noticed that most of the stand-up I watched starred men, but it never occurred to me that there is a belief that women are (innately? culturally? intentionally?) not funny.

After hearing this idea brought up in class during one of our very first meetings, I started thinking about it more. Sure, I don't see that many female comedians, but there's plenty of them in sitcoms, right? And there are female stand-up shows. And I laugh at the jokes women tell. And, I mean, I'm funny, right?!

This potential crisis of identity led me to a Vanity Fair article, titled not "Are Women Funny?" but, quite depressingly, "Why Women Aren't Funny." There's a lot of different perspectives on this issue covered in the article (including a fairly disturbing discussion of the difference between "normal" women and women who do stand-up). The most interesting to me was the discussion that women aren't supposed to be funny, culturally:

it could be that in some way men do not want women to be funny. They want them as an audience, not as rivals.

And this, from Fran Lebowitz:

"The cultural values are male; for a woman to say a man is funny is the equivalent of a man saying that a woman is pretty. Also, humor is largely aggressive and pre-emptive, and what's more male than that?"Really? Is this all humor is? Another pick-up line? Setting aside (and it's a hefty load to place over there) most of the sexism in this line of reasoning, I still don't get it. Is being funny a threatening thing? And even if it is somehow threatening to this traditional view of courtship and relationships, shouldn't we be past it by now?

In a connection that may only make sense in my mind, I was recently listening to a rap/R&B station and heard yet another song (by men) touting the female ideal of being independent. This is becoming a very popular musical theme. (Ludacris: "She makes her own money, pays her own bills" Ne-Yo: "I love her cause she got her own/she don't need mine, so she leaves mine alone" Lil Boosie: "She got her own house/drive her own whip") There have been similar themed songs, but typically from the woman's perspective (Beyonce, TLC, Shania Twain), but I think that having it come from a male perspective changes it, somehow. So, if we're (we being American culture) casting out the traditional idea that men must provide for women, can't we be funny, too?

Saturday, January 31, 2009

The Least Little Toad Frog I Ever Did See

I grew up in the country and one particularly rainy summer, our entire gravel road was filled with both mud puddles and toads half the size of my thumb nail. The title of this blog entry is my neighbor's reaction when my little sister and I, so proud of our discovery, showed her. My neighbor was like a grandma to me, an elderly lady who had grown up in the South. She was full of these colorful phrases and was one of the kindest people I'd ever met. We used to sit for hours on her front lawn, sipping lemonade and talking with her.

Well, she did most of the talking. The truth is, Simon Wheeler's monologue about Leonidas W. Smiley could have been a direct quote of one of my neighbor's stories. For her, everything contained at least two shaggy dog stories. Her descriptions were so circular; she'd begin telling one story, remind herself (without explaining the connection to us) of another story, tell that one, pick back up at the exact place that she left off in the first story, get sidetracked again, and finish after making our head spins so much we were no longer sure what the end had to do with anything at all. But she knew, and it was certainly entertaining to listen to her get there.

When Wheeler starts talking about Jim Smiley, Twain tells us he "never smiled, he never frowned, he never changed his voice from the quiet, gently-flowing key to which he turned the initial sentence, he never betrayed the slightest suspicion of enthusiasm" (171). No wonder Twain was angry at Mr. A Ward for sending him to this man. I can't imagine having sat through all those stories of my neighbor's if she hadn't been absolutely loving every minute of the transaction. Her stories were full of animation and joy. Her voice changed to indicate different characters, different emotions, and she waved her arms around expressively as she gestured to make sure we understood.

Wheeler's turns of phrase and descriptive metaphors make his story come to life. When he says the frog was "whirling in the air like a doughnut," I can see it. And of course the frog hit the floor "as solid as a gob of mud" (174); now it seems like the only reasonable way for a frog to hit the floor. The personification of these outrageous animals is also pure entertainment. When Andrew Jackson "gave Smiley a look as much as to say his heart was broke," I really felt for him. I believe, truly, that Dan'l Webster was "modest and straight for'ard" (174).

But as I read it, I heard it in my neighbor's voice. I couldn't make the description Twain gives of Wheeler's narration match the story itself. This is a story that demands animation. I don't blame the listener for getting up and leaving before hearing about the yellow cow, but if my neighbor had been telling it, I bet he would have stayed.

Thursday, January 29, 2009

The Risks of Satire

The New Yorker tried without much luck to defend the decision to print this cover. America was outraged by the portrayal. This incident clearly illustrates that satire is not always going to work.

Despite that risk, however, several politicians took a "if you can't beat 'em, join 'em" approach to satire. Sarah Palin herself later appeared on Saturday Night Live, standing next to her doppelganger and cracking jokes about her air headed persona. John McCain likewise appeared on SNL, mocking his own campaign strategy in a very amusing QVC satire. Perhaps my favorite example, Huckabee, during the primary season, appeared on the Daily Show and laughed off the fact that it was statistically impossible for him to win his party's nomination.

My question, then, is what makes satire work? It obviously can. Then again, it can obviously fail. And, like most humor, it can work for one person and fail for another.

Swift's proposal mocked not only the attitude that some had about the underprivileged children they saw in the streets, but also Aristotelian argument itself. However, if the reader doesn't recognize that he's using Aristotelian argument, that part of the satire fails. One factor for satire, then, is knowledge. The audience must be knowledgeable about the topic at hand. McCain's QVC skit probably wouldn't be funny to someone who wasn't following the campaign. The New Yorker cover required the reader to be familiar with the recent criticisms of Obama and his wife (that his wife was anti-American, that the two of them participated in a "terrorist fist bump," that Obama was a Muslim). Did this cover fail to gain popularity because it tried to satirize too many things at once? Did it fail because it picked up on some of the comments from a marginalized group of people?

I wonder, then, if in order to be successful, satire must also discuss something that a majority of people are (at least partially) guilty of doing? Though I can't pretend to be an expert on the subject, I'd imagine that most of Swift's contemporary readers would have to feel a pang of guilt while reading the essay. Of course their first reaction would be indignation at the horrendous suggestion that we eat children, but they would then have to compare that defense to the indifference or annoyance they likely felt towards those same children moments before. Though Swift's essay is not a modern piece, it has staying power with readers because the mistreatment of our most impoverished citizens is an issue we still struggle with today.

Another example of a piece that meets these standards is this Onion piece about a man with Hodgkin's Disease that no one "would hold up as a model employee" that is costing his co-workers "$22 per employee per month" because of his health care costs. Most readers should be familiar with the health care problem in America and recognize the satire of it. At the same time, I think that most readers feel that familiar pang of guilt. How many of us have looked at the taxes we pay and complained that they are too high? It also satirizes consumerism's tendency to put a dollar sign to everything, to judge merit in productivity.

I realize that I haven't really made any conclusive statements about much of anything in this post, but I find satire fascinating and confusing. And while it sometimes makes me feel guilty, I usually find it hysterical.

Wednesday, January 21, 2009

Metaphor in "Parson John Bullen's Lizards"

However, as I read through the description of the chaotic climax of "Lizards," I found myself more amused than I typically am with slapstick. I could visualize the scene, and what I visualized was fairly typical of the slapstick I've seen on the screen: the slapstick that isn't funny to me. What then, is the difference? Why does this make me laugh when watching it acted out probably would not?

I'm not certain of the answer, but I think that it has a lot to do with the metaphor. The first part of the story that I marked as particularly funny to me was the description of the pastor "standin' astraddle of [Sut], a-foamin' at the mouf, a-chompin' his teeth--gestrin' with the hickory club--and a-preachin'" (236).

Sut's narrative voice is full of these metaphorical descriptions that bring the action to life in a way that, ironically, actually bringing the action to life wouldn't work for me. Maybe it's because envisioning someone foaming at the mouth and chomping at the teeth while preaching allows for a comical imaginative scene whereas actually seeing this portrayed would just seem over the top and ridiculous.

Another example of this descriptive metaphor occurs when Sut describes one of the lizards diving "head-fust into the bosom of a fat woman as big as a skinned hoss and nigh onto as ugly" (239). Once more, any attempt to physically portray this woman would either fall short of Sut's description or be too ridiculous for me to find funny (unless, perhaps, it was a cartoon rather than live action). Now that I think of it, I find slapstick humor in cartoons much funnier than I do in any live-action portrayal, so the way that I envision these descriptions is probably connected with that.

The metaphor also functions as a supplement to the dialect. Many of the metaphors are region specific. For example, Sut comments that the lizards' climbing made "a noise like squirrels a-climbin a shellbark hickory" and the Pastor slapped himself "about the place where you cut the bes' steak outen a beef." These colorful phrases acted to not only highlight the humorous quality of the action, but to also create a better understanding of the setting, a central point to the plot of the story. This story would not be nearly as funny if it took place in a large city. The fact that these people all know one another and know everything about one another's lives highlights the humility of the Pastor (as well as the initial reason for the lecture he gives Sut).

Thursday, January 15, 2009

What Are You Laughing At?

Freud's theory, however, raised new questions that renewed my interest in the topic. When Freud discusses humor (which he categorizes as different from the comic and joking), he remarks that in making a joke about one's own situation "one spares oneself the affects to which the situation would naturally give rise and overrides with a jest the possibility of such an emotional display." To me, this shifts the focus from "What causes us to laugh" to "What purpose does laughing serve"--a question I find infinitely more interesting.

A quick search query about humor as a defense mechanism led me to this blog entry. In it, "Dr. Sanity" blogs about various levels of defense mechanisms. The first (and most psychologically detrimental) manifests itself in denial and delusions. The second (categorized by immaturity) is marked by projection and "acting out." The third (widespread, but ineffective coping mechanisms) contains things like repression and dissociation.

Humor, however, falls into the fourth category--a category "Dr. Sanity" says is both the most healthy and most mature way of dealing with difficult events. Humor has for it's category-mates altruism and anticipation: both categories that illustrate foresight and useful action.

Humor, then, seems to not only be a defense mechanism, but one of the most sophisticated and productive ones. I think it would be very interesting to look at the types of humor that come about as defense mechanisms and to see if there are any correlations between types of humor and severity of the trauma. (Some of the information that I found while browsing this topic included studies over the humor some Jewish victims used during the Holocaust).

Of course, defense is not the only productive role humor can play in our society. Humor can also make us think about a topic in more depth (as we discussed when watching the George Carlin clips) or perpetuate ideas in an attention-grabbing way (the first thing that comes to mind is the anti-smoking campaign that often uses humor to get across its message).

I may be starting to venture into a new topic now, but I think that this last point also brings up a clear concern with the way that humor is used in our society. As a critical viewer of advertisements, I have realized that many ad campaigns use humor in place of substance. Instead of illustrating the worth of a product, many commercials rely completely on making us laugh. The most obvious example to me would be the beef jerky commercials with the Sasquatch; there's nothing in these commercials that should make someone want beef jerky or that illustrates why this beef jerky is the best quality, value, etc. The primary goal of the commercial is to make us laugh and, presumably, to remember them (ironically, I've forgotten the brand name). I would like to look into it more, but I assume that this advertising strategy is effective or it would not be used so often. If so, does this highlight some of the risks of humor? Can it be a distraction from substance? Shouldn't we, as a society, think more critically about the ideas being pitched to us?